Herewith my column from 2012. (Shameless plug: If you appreciate this kind of long-form writing, you’ll like reading my book, ‘On Motorcycles: The Best of Backmarker’. Buying a copy would be a great way to tip your hat… and me.)

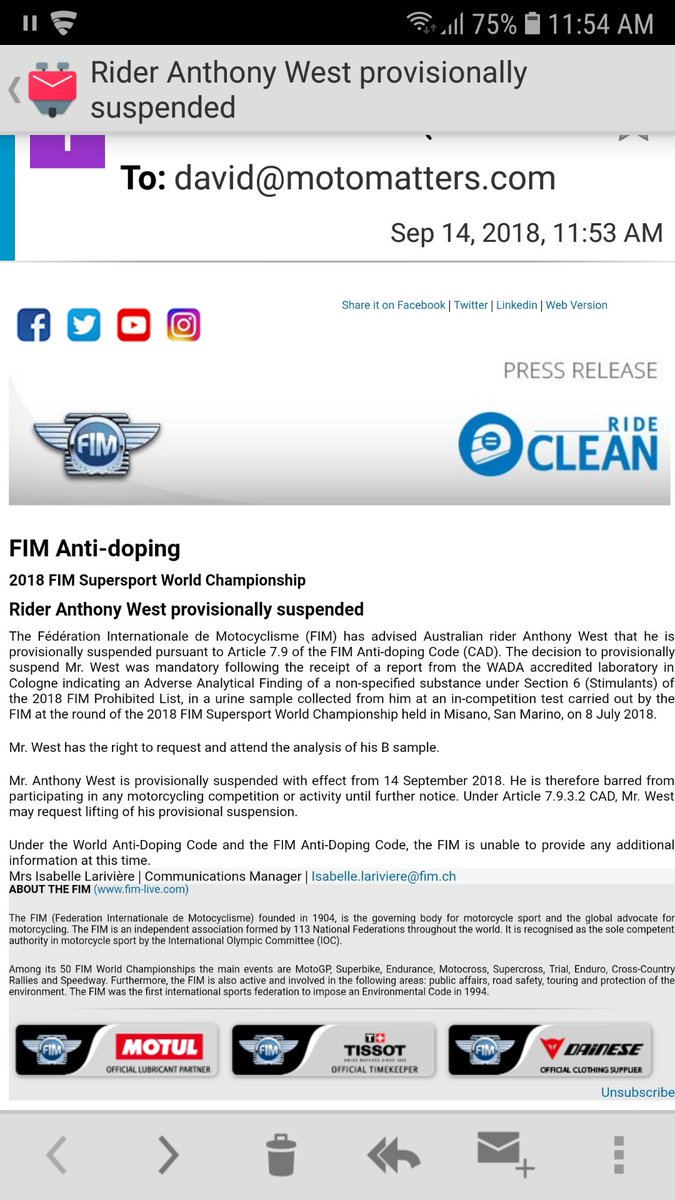

An Australian guy, named Anthony, tests positive in a random drug test.

That sounds like the beginning of an old joke, where the punch-line is 'Anthony Gobert'.

But Ant West's retroactive disqualification from the French Moto2 event (where the sample was taken, in May) and 30-day ban (beginning October 30, in the wake of the recent ruling by the FIM's International Disciplinary Court) are not the same thing as the "Go-Show's" repeated recreational drug transgressions. Here's why...

West tested positive for methylhexaneamine. This 'drug', which is extracted from geranium plants, is a mild stimulant that wears off in hours. It's similar to caffeine. No expert believes it's a meaningful performance aid even in sports like running or rugby. Methylhexaneamine certainly didn't influence the results of the French Moto2 race, in which West finished 7th, almost one second behind Pol Espargo and six seconds ahead of Max Neukirchner.

Methylhexaneamine confers only a trivial advantage, but it's actually a pretty frequent drug 'catch' in doping controls. Want to know why?

It's a common ingredient in body-building and training supplements. Putting it in training supplements isn't any different than chugging a Muscle Milk shake followed by an espresso shot before hitting the gym. (That, in fact, is my formula.) The makers of those supplements are under no real pressure to even list all their ingredients, nor is there a standardized nomenclature for ingredients. An athlete that wanted to avoid methylhexaneamine would have to look for...

Geranium -oil, -extract, -flower, -stems, -leaves, Methylhexaneamine; Methylhexanamine; DMAA (dimethylamylamine); Geranamine; Forthane; Forthan; Floradrene; 2-hexanamine, 4-methyl-; 2-hexanamine, 4-methyl- (9CI); 4-methyl-2-hexanamine; 1,3-dimethylamylamine; 4-Methylhexan-2-amine; 1,3-dimethylpentylamine; 2-amino-4-methylhexane; Pentylamine, 1, 3-dimethyl-.

...and that's not even an exhaustive list.

West's 30-day ban (which he has until Sunday to appeal) has the effect of denying him a start in the season finale in Valencia. I'm not sure if, according to FIM rules, he can partake in early post-season tests or whether the ban applies to competition only. Either way, though, it's bullshit.

The irony of West's ban, in a sport in which riders routinely expose themselves to deadly risk, and where there is a traveling doctor in the paddock at all times whose main duty is to provide pain-killing drugs to riders who want to compete with injuries, should not be lost here. That irony is doubled by the fact that West's ban is for a mild stimulant. Presumably he'd've been fine if he'd glugged down a Monster Energy or Red Bull, since those companies are major sponsors.

The FIM and MotoGP have voluntarily acquiesced to WADA, the World Anti-Doping Agency. Thus, the unique drug control 'needs' of motorcycle racing have been replaced by WADA's one-list-suits-all approach. A big part of the FIM's embrace of WADA actually goes back to the chip motorsport has on its shoulder about whether racers are athletes. ("Look, our guys have to pee in a cup just like Lance Armstrong.")

WADA itself warrants some skepticism. What began as a legitimate and generally-agreed-as-necessary quasi-independent organization supervising doping control at the Olympics quickly became an IOC-style old-boys club of its own.

To grow, WADA convinced non-Olympic sports governing bodies to sign up; the FIM pays WADA dues and relies on its testing and protocols. (Half WADA's funding comes from sports governing bodies, and half comes from national governments.) Now WADA, an organization that justifies its existence by catching athletes who have an 'adverse analytical finding', has an incentive to create the longest-possible list of banned substances -- and in effect to ban substances on the flimsiest evidence that they could confer an advantage in any of hundreds of sports.

The range of sports that have now agreed to turn over their doping controls to WADA is so diverse that athletes face the risk of being banned for the accidental use of drugs that put them at a disadvantage. Stimulants are banned across the board, so they're banned in shooting sports. Jockeys are tested for all manner of steroids.

It would be great if common sense could prevail, and the FIM and MotoGP could consult a few experts and -- once they'd determined that West didn't gain an advantage or even knowingly cheat -- void WADA's finding. It would be great if the FIM told WADA, "Hey, you give us all the drug reports, and let us decide who's cheating." Instead, WADA and the FIM spent five months smelling and tasting West's piss, holding the test tube up to the light, and then announced West's 30-day ban.

The Lance Armstrong debacle (and BALCO before that) proves that in sports where doping can and does influence results, WADA in particular and doping control, generally, is still playing catch up to the cheaters. Motorcycle racing needs to police the use of recreational drugs for safety's sake, and to keep an eye on performance-enhancing drug technology. But WADA's exhaustive list of banned substances and the FIM "court's" decision in West's case is bullshit