Here’s the writeup I sent to Bike, which ran under the title, “This Zero is really something”

Last summer, oil sold for over $125 a barrel and ecologists fretted over the prospect of the arctic ice cap melting for the first time in history. No surprise, then, that there was a sharp increase in interest in electric vehicles. Go ahead, roll your eyes–I don’t blame you. Because so far, electric vehicles have been… boring.

You’re imagining golf carts or those rolling chairs old, fat chain-smokers use to troll the aisles at Wal-Mart. You think that if–thanks to fossil fuel shortages or pollution control–we’re ever restricted to two-wheeled versions of those, please shoot me now.

That’s what I thought, too. Then through a friend of a friend, I was allowed into the skunkworks at Zero Electric Motorcycles, near Santa Cruz, California. Santa Cruz was one of the hotbeds of the mountain bike revolution in the’80s and it’s just over the coastal hills from Silicon Valley. Appropriately, Zero tapped into both cultures, combining ultra-lightweight design and components from the bicycle industry with sophisticated software and high-tech engineering that maximizes battery life. Zero definitely had that high-tech startup company, we’ll-all-soon-be-millionaires atmosphere.

Another thing in the atmosphere was the smell of cold pizza. That odor, and a very large punching bag in the middle of the assembly area, told me all I needed to know about nerds putting in long hours and occasionally getting real frustrated.

But the work’s paying off, in the form of the Zero ‘X’ electric motorcycle. It might look a bit odd and spindly, but it’s the first electric vehicle–with two- or four-wheels–with a performance envelope the meaningfully threatens its gas-powered rivals.

Whose idea was this? Meet Neal Saiki, Zero’s Chief Technology Officer. After graduating from California Polytechnical University with a Masters degree in Aeronautical Engineering, Saiki went to work for National Aeronautical and Space Administration. Although his principal work was in high altitude research vehicles, he was exposed to NASA research & development projects with terrestrial applications too–specifically projects on zero-emissions vehicles. In the course of that work, he became familiar with a type of small, rare-earth-magnet electric motor developed to power secret stuff, like torpedoes.

“I always thought,” he told me, “that if they released that technology for civilian applications, it would make a great motorcycle motor.”

An avid motorcyclist and mountain biker, Saiki bailed from NASA and switched to a different–still zero-emissions–track. He started designing downhill mountain bikes. The frames he designed for Haro, Santa Cruz, and Mountain Cycle were used to win World Championship-level races. Those projects also familiarized him with the range of high-quality, ultra-light components being created for the bicycle market, and the specialist fabricators in the Silicon Valley region.

When those lightweight motors became available, he realized that, as he put it, “All I needed was a battery, and I could make an electric motorcycle.” It wasn’t really that simple, the lithium-ion batteries that power things like your laptop generate a lot of heat. Saiki knew his battery would have to dump about 300 amps of power at peak load. Remember those Mac laptop batteries that were recalled a couple of years ago? They were ‘experiencing thermal runaway’–that’s what high-tech engineers call catching fire–at loads two orders of magnitude lower.

Saiki developed and patented a way of packing the cells and controlling them that makes his ‘Zenergy’ battery the smallest/lightest/most powerful/coolest one ever. I picked one up in his workshop; it’s roughly the size and weight of a car battery. But it will power a 20 horsepower motor at full load for almost two hours. It’s environmentally friendly, too. It contains no toxic metals and is rated for normal landfill disposal.

20 horsepower may not sound like much, but it doesn’t tell nearly all the story. Electric motors make peak torque at all rpm. And they make a lot of it. The Zero X weighs 140 pounds–a hundred pounds less than a 250cc four stroke motocrosser. It’s geared for a top speed of about 55mph, and it will stick with one of those 250s in a drag race until it reaches its top speed.

It’s interesting, to say the least, to ride. It’s set up like a twist-and-go scooter, with footpegs but no foot controls. There’s a rear brake on the left ’bar, and front brake on the right one, as well as a “throttle” on the right twistgrip. There’s no gearbox.

The bike has a sort of key that operates a master power switch. The Zero dudes call that ‘arming’ the bike. When you turn that key, a row of LEDs lights up to indicate the amount of time you have left on the battery. The bike doesn’t make any sound at all when it’s armed, which is potentially dangerous. If you reflexively blip the throttle, it’ll take off on you. That’s been a problem when one person hands the bike off to another.

I rode it in the street and around Zero’s workshop. I thought it handled about like a similarly-proportioned dirt bike, although I have to say that the light weight and silent running would sure be easy to get used to. In the full power/full speed modes, the motor feels a lot more powerful than 20 hp. Throttle response is instant, and it will lift the front wheel with very little provocation. The closest thing I can relate it to might be a 250cc two-stroke trials bike.

Although a few hundred of the bikes have been sold in 2008, no magazine’s had access to a bike for a full test until now. I twisted arms until the company agreed to have someone meet me at the Apex supercross training track east of Los Angeles. It was a tricky thing for me to test, since my background is road racing, and because there’s nothing to compare it to. To get an expert’s second opinion, I brought in the best dirt rider on my speed dial: Micky Dymond.

Micky was a little weirded out by the Zero at first. The brakes felt soft, and the ‘throttle’–actually a twistgrip connected to a rheostat–had some play in it. After a few cautious laps, he came in and said, “It’s awkward, and strange, without noise it’s hard to gauge my speed, and there’s no engine braking.”

Then, it started to grow on him. “At first, when I opened the throttle a little bit, it just exploded. But it’s completely linear. And I thought I needed more brakes, but it’s so light that I can brake much deeper into the corners.”

The standard fork and shock are adjustable for preload only. “You can definitely bottom them out,” said Micky, “But you can bottom anything out; these aren’t too bad.”

He also praised the overall balance of the bike. Like every serious rider who’s tried it, an hour into his test ride, he wanted one of his own, so that he could practice in areas near his home that were open to mountain bikes but off-limits for motorcycles.

Then, emboldened to try some bigger jumps, Micky went out and promptly blew the rear shock apart. Oh well. In fairness, no one at Zero claims their bike’s a motocrosser. The bike(s) we tested were standard 2008 versions. The frame is welded alloy, with geometry similar to a downhill mountain bike’s. The chain, suspension, wheels and tires look like downhill bike components, but in fact all of them are custom-engineered to Zero’s specs. The bike can be ordered with your choice of two motors, one about 10% more powerful than the other.

As tested, the Zero X is intended for use as a trail bike. Based on my own experience and what I’ve seen, I believe that I could handle more challenging terrain on the Zero than I could on a good 250cc four-stroke trailie. It would make a great green-laner, or training bike for any motorcycle racer. In the state of California, electric motorcycles that are limited to speeds under 30 miles per hour–as this bike is, at the flick of a switch–are legally treated as bicycles, making it road-legal even though it lacks lights, a speedo, or horn.

A Supermoto-styled commuter bike, dubbed the Zero ‘S’, will be released soon (it may have been unveiled before this reaches the newsstands.) It will have lights and a speedometer and be fully road-legal in the U.S. As this story went to press, the details were still secret, but Neal told me that the street bike will have a 50% larger battery and be geared for a top speed of 70 miles an hour. That should yield a minimum range of 150 miles; potentially a lot further, depending on your average speed.

The reason that range is dependant on speed is that 80% or more of the work done by a motorcycle engine is displacing air, and air resistance increases with the square of velocity. That’s why the fuel mileage of the motorcycle you’re riding these days plummets as your speed increases.

The remainder of the work done by the motor is almost all proportional to the mass being accelerated or lifted up hills. That’s why Neal Saiki was obsessed with keeping the first Zero as light as possible–and why it’s at least 100 pounds lighter than a competing gas-engined motorcycle. Keeping it light also takes pressure off the brakes and suspension.

Therein lies the fundamental dilemma: You’d like to have a larger battery for more range, a more powerful motor, a gearbox, adjustable fork and shock… but for every pound you add in the form of those improvements, you pay at least a 12-ounce tax in sapped performance.

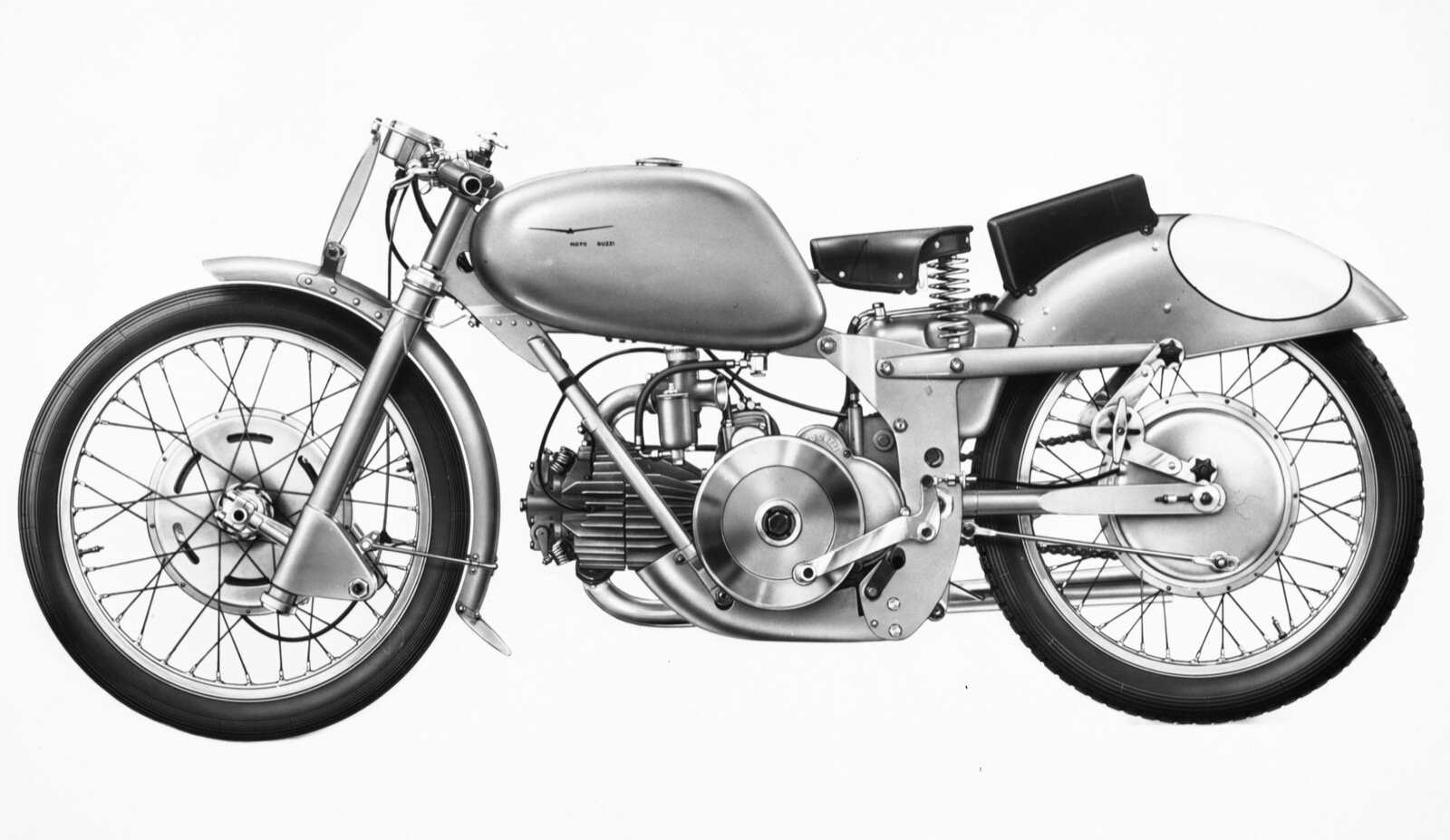

Think of the evolution of sport bikes: in the early 1960s, a top rider on a Manx Norton could lap the TT course at 100 miles an hour. That was on a bike that made just under 50hp and weighed about 300 pounds. Over the next 40 years, despite course improvements and huge leaps in tire, suspension, and brake technology, the course record improved only 25%. That was all, even though the bikes being raced in the top TT classes tripled their horsepower and fuel consumption.

Right now, even Saiki’s absolutely state-of-the-art Li-ion battery has only 10% of the energy density of gasoline. That’s to say fully charged, it contains only 10% of the energy that you could extract from 40 pounds of gasoline.

Because of that, the right design for a new electric motorcycle can’t draw much from its gas-powered predecessors. (And it’s why the Tesla electric sports car is doomed to failure, despite intense media hype. Tesla is using a very conventional car’s rolling chassis. It’s far too heavy. And since the car company doesn’t have access to Saiki’s–literally!–cool battery technology, it has to water-cool the batteries, adding even more weight and water-pump drag.)

Luckily, Saiki understands keeping things light. In university, he led a team that built the world’s first human-powered helicopter. It had wings as long as a Boeing 737’s and weighed 97 pounds. Most the Zero’s frame is made of ultra-thin wall square-section alloy tubing. Take the battery out of it, and it weighs only 50% more than a downhill mountain bike.

Right now, there are still only 30 employees at Zero. Although virtually every component is custom-designed to Saiki’s specs, Zero is a motorcycle assembler, not a manufacturer. All the components are built elsewhere and shipped in to the small Santa Cruz workshop, where bikes are assembled one by one. That system’s worked fine so far, allowing the company to sell a few hundred bikes over the Internet. But the potential market for a commuter version’s easily 10,000+ units/year. That’s a lot of Zeros, with capital ‘Z’.

Looking back at groundbreaking inventions, there have been plenty of companies with great patents that failed. The plodding patience, attention to detail, discipline and long attention span required to ramp up mass production, organize a dealer network, and build a global brand are not found in brainstorming inventors.

That was on my mind when Zero delivered three bikes for me to test, and they arrived dirty. None of them had fully charged batteries, or fresh tires. If you want to build an electric dirt bike, it would be a completely wrongheaded approach to just take a Honda CRF and replace the gas tank with a battery, and swap motors. If you want to build an electric motorcycle company, however, it’d be wise to learn that when Honda delivers a test bike, it’s pristine.

I put it to Saiki and Gene Banman, the company’s CEO, that the Silicon Valley business model is not to commercialize your invention, anyway. Rather, you lock up the patents and prove your concept, then wait for an established company to buy you out. Both men denied that was their strategy. But I can guarantee you that it will not be long before Honda and Harley-Davidson come a-courtin’ and when they do they won’t bring flowers and chocolates, they’ll bring very large cheques with a lot of small ‘z’ zeros.

In the long run, the writing’s on the wall for gasoline-powered motorcycles. We could, of course, keep using them for decades, until the financial and/or environmental cost of burning gas finally becomes unbearable. At that point, as imperfectly as free markets work, someone will sell us an alternative.

But what if the solution wasn’t adopted because gas was impossible to afford or because we’d triggered environmental chaos? What if it was just better? And happened to be clean... Looking at the Zero X today, I’m now betting that we’ll go electric by choice, not necessity.

OK, so I got a few things wrong

I suppose Tesla wasn’t doomed to failure. I was wrong that Zero would become an acquisition target. And I was wrong that increasing fuel prices would be a significant factor in influencing the uptake of EVs.

But I was right about a lot.