Eyewitnesses

Bertis ‘Bert’ Lanning was 37 years old when the ‘47 Gypsy tour rode into Hollister. As a mechanic in a local garage, he had direct contact with many of the bikers involved.

"I worked in Hollister, at Bernie Sevenman’s Tire Shop, right on the main street. I had motorcycles myself, a Harley ‘45, and a Triumph. I’m 88 now and my eyes aren’t good enough to ride anymore, but I’ve still got a bike in my garage!There was a mess of ‘em. Back then, beer always came in bottles, and there were quite few of them broken in the streets, so the bikers were getting flat tires. They’d bring them into the shop, either to get them fixed, or they’d want to fix them themselves.

Eventually it got so crowded in and around the shop that guys were fixing tires out in the street, running in and out to borrow tools. Maybe a couple of tools went missing. Anyway, my boss got nervous and told me to close up the shop. I thought that was great, because I wanted to get out there myself.

Main Street was packed, but it wasn’t nearly as bad as the papers said. There was a bunch of guys up on the second floor of the hotel, throwing water balloons. I didn’t see any fighting or anything like that. I enjoyed it. Some people just don’t like motorcycles, I guess."

Bob Yant owned an appliance store on Hollister’s main street. Back then, appliances were built to last, and so was Bob: He still works at the store every day.

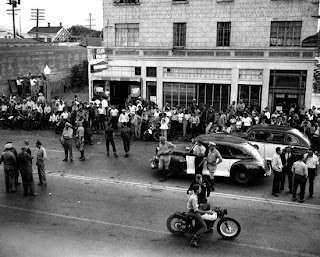

"In 1947, I had just bought into my Dad’s electrical contracting and appliance business. We had a store right on San Benito (street). There were motorcyclists everywhere; they were sleeping in the orchards.Our store was open that Saturday. Guys were riding up and down Main Street, doing wheelies. The street was full of bikes, and the sidewalks were crowded with local people that had come down to look. Actually, it was bad for my business; my customers couldn’t get to the store. It was so slow that I left early, and let my employee lock up.

On Sunday, I went to the hospital, to visit a friend. There were a bunch of guys injured, on gurneys in the hallway, but I think they were mostly racers. There must’ve been about 15 of them, which was quite a sight in such a small hospital.There was no looting or anything; I was never afraid during the weekend. You know we had a few little hassles even when the motorcyclists weren’t in town. I think some guy rode a bike into ‘Walt’s Club’ (a bar) or something, and somebody panicked. The Highway Patrol came en masse and cleared everybody out.

The day after everyone had left, near my store, there were two guys taking a photograph. They brought a bunch of empty beer bottles out of a bar, and put them all round a motorcycle, and put a guy on it. I’m sure that’s how it was taken, because they wanted to get high up to take the shot, and they borrowed a ladder from me. That photo appeared on the cover of Life magazine. (Author’s note: I do not think that Life ever ran the Hollister story on the cover.)

Not long after that, they turned the little racetrack into a ballpark."

Catherine Dabo and her husband owned the best hotel in Hollister. When bikers were being demonized in the media, she always defended them.

"My husband and I owned the hotel, which also had a restaurant and bar. It was the first big rally after the war. Our bar was forty feet long, and a biker rode in the door of the bar, all along the bar, and through the doors into the hotel lobby!We were totally booked. Every room was full, and we had people sleeping in the halls, in the lobby, but they were great people; we had more trouble on some regular weekends!

I was never scared; if you like people, they like you. Maybe if you try telling them what to do, then look out!The motorcycles were parked on the streets like sardines! I couldn’t believe how pretty some of them were.

I was great for our business; it gave us the money we needed to pay our debts, and our taxes. they all paid for their rooms, their food, their drinks.

They (the press) blew that up more than it was. I didn’t even know anything had happened until I read the San Fransisco papers. The town was small enough that if there had been a riot anywhere, I’d have known about it! I had three young children, we just lived a few blocks away, and I was never scared for them.

I think the races were on again in ‘51. My husband and I always stood up for the bikers; they were good people."

Gil Armas still rides a 1947 Harley ‘Knucklehead’. He competed in dirt track events, and later sponsored a number of speedway riders.

"Back then, I was a hod carrier; I worked for a plastering outfit in L.A.. I had a ‘36 Harley, and rode with the Boozefighters. We used to hang out at the ‘All American’ bar at Firestone and Central. Lots of motorcycle clubs hung out there, including the 13 Rebels, and the Jackrabbits.Basically, we just went out on rides. Some of us went racing, or did field meets, where there events like relays, drags; there was an event called ‘missing out’ where you’d all start in a big circle, and if you got passed, you were out.

At first, most of our racing was ‘outlaw’ races that we organized ourselves, but a few years later, a lot of us went professional, and raced in (A.M.A.-sanctioned) half miles and miles. I retired (from racing) in ‘53.

I just went out to Hollister for the ride. A couple of my friends were racing. My bike was all apart, and I threw it on a trailer and towed it up there; I didn’t want to miss out on the fun. I ended up sleeping in the car.We started partying. There were so many motorcycles there that the police blocked off the road. In fact, they sort of joined in. There were four of them in a jeep. We sort of had a tug-of-war, with us pushing it one way, and them pushing it the other. Tempers flared a little when somebody stole a cop’s hat, but it all blew over. There was racing in the street, some stuff like that, but the cops had it under control.

Later on, the papers were telling stories like we broke a bunch of guys out of jail, but nothing like that happened at all. There were a couple of arrests, basically for drunk-and-disorderly; all we did was go down and bail them out. In fact, a few of the clubs tried to force the papers to print a retraction. They did write a retraction, but it was so small you’d never see it.

The bar owners were standing out front of the bars saying ‘Bring your bike in!’. They put mine right up on the bar.

On Sunday, the cops came back with riot guns, and told us all to pack up and leave. At first, we just sat on the curb and laughed at them, because there was no riot going on, but we all left anyway.In those days, if you rode a motorcycle, then anybody that rode a motorcycle was your buddy. We (Boozefighters) were just into throwing parties."

August ‘Gus’ Deserpa lived in Hollister. He is the smiling young man seen in the background of the famous ‘Life Magazine’ photo.

"I was projectionist by trade. I worked at the Granada Theater, which was on the corner of Seventh and San Benito. I would have got off work around 11 p.m.. My wife came to pick me up, and we decided to walk up Main Street to see what was going on. I saw two guys scraping all these bottles together, that had been lying in the street. Then they positioned a motorcycle in the middle of the pile.

After a while this drunk guy comes staggering out of the bar, and they got him to sit on the motorcycle, and started to take his picture.I thought ‘That isn’t right’, and I got around against the wall, where I’d be in the picture, thinking that they wouldn’t take it if someone else was in there. But they did anyway. A few days later the papers came out and I was right there in the background.

They weren’t doing anything bad, just riding up and down whooping and hollering; not really doing any harm at all."

Marylou Williams and her husband owned a drug store on Hollister’s main street.

"My husband and I owned the Hollister Pharmacy, which was right next door to Johnny’s Bar, on Main Street. We went upstairs in the Elks Building, to watch the goings-on in the street. I remember that the sidewalks were so crowded that we had to squeeze right along the wall of the building.Up on the second floor of the Elks Building, they had some small balconies. They were too small to step out onto, but you could lean out and get a good view of the street. I brought my kids along; I had two daughters. They were about 8 and 4 at the time. It never occurred to me to be worried about their safety. We saw them riding up and down the street, but that was about all; when the rodeo was in town, the cowboys were as bad."

Harry Hill is a retired Colonel, USAF. He was in visiting his parents in Hollister during the 1947 riots.

"I was in the Service then, but I was home for the long weekend. Hollister was a farming community back then. The population was about 4,500 or so. Now it’s a bedroom community for Silicon Valley, and the population is about 20,000.Before the war, they had motorcycle races out at Bolado Park, about 10 miles southeast of town. I believe the big event was a 100-mile cross country race.

Back then, the AMA had a thing called a Gypsy Tour; people would come from all over on motorcycles. Besides the races there were other contests: precision riding, decorating motorcycles.I liked motorcycles; I started riding in about 1930, and at different times had both Harleys and Indians. I stopped riding when I enlisted in the Air Force, in about ‘41, so my bikes were old ‘tank shift’ types.

Back then, the race weekend wasn’t necessarily the biggest thing in town, but it was as big as the rodeo, or the saddle horse show. It seems to me that there were always two or three people killed during those weekends; people racing, and riding drunk, but things changed after the war; they got a lot rowdier.

In ‘47, I was still on active duty. I guess I was quite a bit more disciplined than the average biker that rode in that weekend. It was such a madhouse; my parents were elderly, too, and I didn’t feel it was right to leave them alone, so I stayed around the house. I sure heard it, though.

On Sunday, I took a look around. It was a mess, but there was no real evidence of any physical damage; no fires, or anything like that.

There seemed to a be a lot more drinking going on when the motorcycle boys were in town, than when the cowboys were in town. When the motorcycle boys got rowdy, we used to say ‘Turn the cowboys loose on ‘em!’.

Years later, I started riding again. Frankly, I was worried about the image we had as motorcyclists: the Hell’s Angels, the booze, the whores... (motorcycling’s) reputation got real bad. And there continued to be bad publicity at places like Bass Lake, where there was a big annual biker gathering. But I rode because I loved it. My last bikes were a Kawasaki Mach III in the seventies, and a Kawasaki 1000, which I sold in 1990."

Jim Cameron is still a motorcycle racer, riding a Jeff Smith-built BSA Gold Star in vintage motocross events. "Because of my age," he laughs, "AHRMA will only let me compete in the ‘Novice’ class!"

"I was a Boozefighter. The Boozefighters were formed a year or so earlier. Wino Willie had been a member of the Compton Roughriders. They had gone to an AMA race, a dirt track, in San Diego. In between heats, Willie, he’d been drinking, of course, started up his bike and rode a few laps around the track, just for laughs. Eventually they got him flagged off.

The Roughriders sort of kicked him out of the club for that; they felt he had embarrassed them.Willie decided that if they couldn’t see the humor in that, he’d start his own club. Back then a bunch of us hung out at a bar in South L.A., called the All American. Several clubs met there: the 13 Rebels, the Yellowjackets, anyway, Willie was talking to some other guy about what to name the club, and there was an old drunk listening in. This old drunk pipes up "Why don’t you call yourselves the ‘Boozefighters’.

Willie thought that was funny as hell, so that was the name.The name Boozefighters was misleading, we didn’t do any fighting at all. It was hard to get in; you had to come to five meetings, then there was a vote, and if you got one blackball, you were out. We wore green and white sweaters with a beer bottle on the front and ‘Boozefighters’ on the back.

Back then, I was 23 or 24 I guess, I had just come out of the Air Force. I’d been in the Pacific, but Willie and some of the others had been paratroopers over in Europe. They’d had it pretty rough in the war. I had an Indian Scout, and a Harley ‘45 that I used as a messenger.

Back then, the AMA organized these ‘Gypsy Tours’. One was going up to Hollister on the Independence Day weekend. That sounded good, so a bunch of us decided to ride up there.

We left L.A. Thursday night, and rode through the night. I think my Scout only went about 55 miles an hour, so it took quite a while. I think we rode until we were exhausted, and stopped to sleep for a few hours in King City. It was about 6 a.m. when I woke up. It was pretty cold, and when the liquor store opened, I bought a bottle, which I drank to try to get warm. Then I rode on in Hollister.It was about 8:30 a.m. on Friday morning when I arrived there.

I was riding up the street, and I see this guy, another Boozefighter come out of a bar, and he yells ‘Come on in!’. So I rode my bike right into the bar. The owner was there, and he didn’t seem to mind at all. He could see I was already pretty drunk, so he wanted to take my keys; he didn’t think I should go riding in my condition. The Indian didn’t need a key to start it, but I left it there in the bar the whole weekend.

I don’t think there were more than maybe 7 of us from the L.A. Boozefighters there. There were some guys from the ‘Frisco Boozefighters, too. One of our guys had a ‘36 Cadillac. He used that to tow up our trailer. We had a trailer with maybe fifteen or sixteen bunks in it; stacked three high on both sides. Basically, we’d drink and party until we crapped out, then we’d go in there and sleep it off.

They claimed there were about 3,000 guys there. I think most of them went out to the dirt track races outside of town, but we didn’t. We were having fun right there. The street was lined with motorcycles, and the cops had blocked it off. Basically, guys were just showing off; drag racing, doing power circles, seeing how many people they could put on one bike, and we were just watching and laughing.

The leader of the ‘Frisco Boozefighters was a guy we called Kokomo. He was up in the second or third floor window of the hotel, where there was a telephone wire that went out across the street. He was wearing a crazy red uniform, like a circus clown, and he was standing in the window pretending like he was going to step out onto the wire, like a tightrope walker. It was funny as hell.

There were a couple of cops there, but they were playing it cool. Basically, they didn’t arrest anybody unless they did something to deserve it. The one Boozefighter I can think of that got arrested was a ‘Frisco guy. Some of them had come down in a Model T Ford. It was overheating, and while they were driving down the street, he was trying to piss into the radiator. Anyway, they arrested him, and Wino Willie went down to try to get him out; he was pretty drunk at the time, so they arrested him, too. But they let them both out after a few hours.

Around Saturday night I started to sober up. After all, I had to ride home on Sunday. I guess I, got my bike out of the bar and headed home at about 4 p.m. on Sunday. It definitely wasn’t as big a deal as the papers made it out to be."

John Lomanto owned a farm a few miles from Hollister. He was an avid motorcyclist, and a well-known local racer.

"I worked with my father on our farm, which was just a few miles from Hollister. We grew walnuts, apricots, and prunes. I had a ‘41 Harley, and was one of the original members of the Hollister Top Hatters Motorcycle Club. In fact, the first few meetings were held in one of our barns, but later on we rented a clubhouse in downtown Hollister. We met three times month. We were a real club, with a President, a Secretary, a Treasurer, and all that. Our wives came, too. Our uniform was a yellow sweater with red sleeves.

There were a few races going on that weekend; I think there was a 1/2 mile race, and a TT. I didn’t go to the races, but I rode my bike downtown.It was pretty exciting. The main street was blocked off, and the whole town was motorcycles all over the place. Everybody had a beer in their hand; I can’t say there weren’t a few drunks, but there was no real fighting.”

Hollister Redux

About ten years later, Bike Magazine asked me to write a feature on Hollister, and while I was visiting the town, another witness surfaced...

The riot took place 75 years ago. I did my original research, interviewing about a dozen eyewitnesses, almost 25 years ago, and even then it was hard to separate the witnesses’ genuine memories from tales they’d told and retold, or read. I hardly expected anything new to come to light when I returned to Hollister in 2008.