Thanks to The Vintagent, I see that Mecum Auctions is selling off the “Roadog” motorcycle—one of two made—that had been on display at the soon-to-be-defunct National Motorcycle Museum in Anamosa, IA. That encouraged me to repost this story that I wrote about six years ago. (If you read it then, please indulge me. MG)

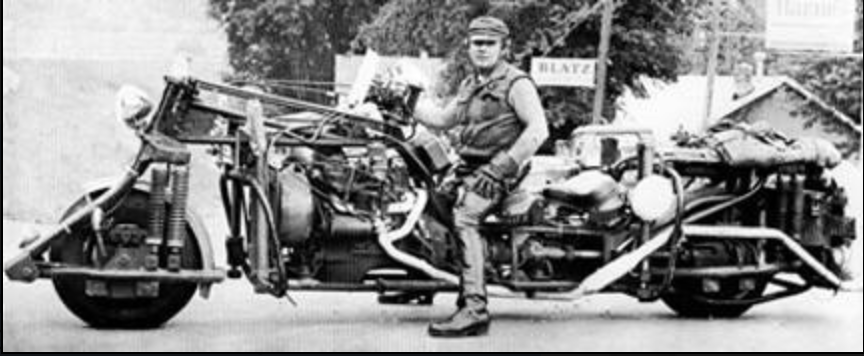

I can think of only two motorcycle photos that are permanently etched in the imaginations of non-motorcyclists: Rollie Free, setting a land-speed record in a borrowed bathing suit; and 'Wild Bill' Gelbke, astride 'Roadog' -- his home-made 17'-long, 3,280 pound motorcycle.

The photo of Bill Gelbke was taken in 1970, by a small-town newspaperman named Ralph Goldsmith. He was the editor and proprietor of the Bascobel (Wisconsin) Dial.

A few years ago, while I was writing a second edition of my Bathroom Book of Motorcycle Trivia, I decided to include a little section of four of five days'-worth of trivia about Gelbke and Roadog. On the spur of the moment I wondered what ever happened to the photographer, and whether he'd ever been compensated for the countless times his image was reproduced on posters, bar mirrors, in books and magazines, on t-shirts and God-knows-where-else.

I did a web search for 'Ralph Goldsmith'. And while I was a few years too late to reach him, I did reach his son and namesake, who is himself already 60.

Ralph Jr. told me quite a story about the image, which is definitely a part of Goldsmith family lore.

"My dad got a call from a bartender, who worked on the edge of town," he told me. "He said, 'You've gotta' come and see this bike'."

Presumably Gelbke was on one of his many relatively aimless rides. (According to legend, he rode 20,000 miles in the first year after building Roadog. He'd grown up in Green Bay and had a shop on Cicero Avenue in Chicago, so I suppose Roadog was seen quite a bit on the roads of Wisconsin. And judging from what I've read about him, Wild Bill probably stopped at pretty much ever roadhouse.)

Anyway the newsman, Goldsmith Sr., hopped in his car, carrying his trusty 120 roll-film camera. Like all newspapermen of the period it was loaded with black and white film. Since the Bascobel Dial reproduced photos with an 85-line halftone screen, the 2 1/4 inch wide negative was already overkill; it was probably loaded with something like 400 ASA-rated Kodak Tri-X.

He got to the bar in time, and snapped a picture of Wild Bill Gelbke astride his monstrous bike. The photo ran in the next weekly edition of the 'Dial'.

Ralph Jr. told that some time later, his dad got a call about the photo. I didn't think to ask whether someone had seen it in the Dial, or whether (more likely) it went out on a wire service. Whatever the case might've been, Mr. Goldsmith thought that his image, having run in the Dial, had outlived any immediate utility. So without thinking anything of it, he put the only negative he had in an envelope and mailed it to the caller. He didn't ask for payment, specify one-time rights, or even bother to keep track of who he was sending to.

His son told me that it was years before he realized that it had been reproduced and re-reproduced as a poster and in countless other ways. By then, it seemed impossible to track his negative back down. To make matters worse, the newspaper used a very impermanent printing process, so Goldsmith's print had faded and discolored.

Ralph Jr. told me that his dad had been an excellent photographer and that he remembered that the negative was pin-sharp; poster quality. I could tell from talking to him that the family had long realized that if only dad had kept that negative, they could have made a pretty penny from licensing fees.

Oh well. In everyone's life there has to be one great lost opportunity. Ralph Goldsmith's was the time he mailed off that useless negative to some faceless stranger.